As I post this blog, we’re sitting in the Dubai International Airport, just a few short hours from reconnecting with our loved ones back in the States. For the times where we’ve had intermittent Wi-Fi, or quick connections to make and no time to check in, please know that we are all safe – at about 8:00 in the morning in Dubai, we’re thinking of all of you finishing dinner, sitting with loved ones, and preparing for the Friday that, for us, has already begun.

Our journey home has been long and emotional in many ways, but the thought of being home is thrilling and we cannot wait to share our experiences with all of you so soon. Plot twist: the blog doesn’t really stop until you’re holding us in your arms, so make sure to keep checking until the last minute – there might be more to come.

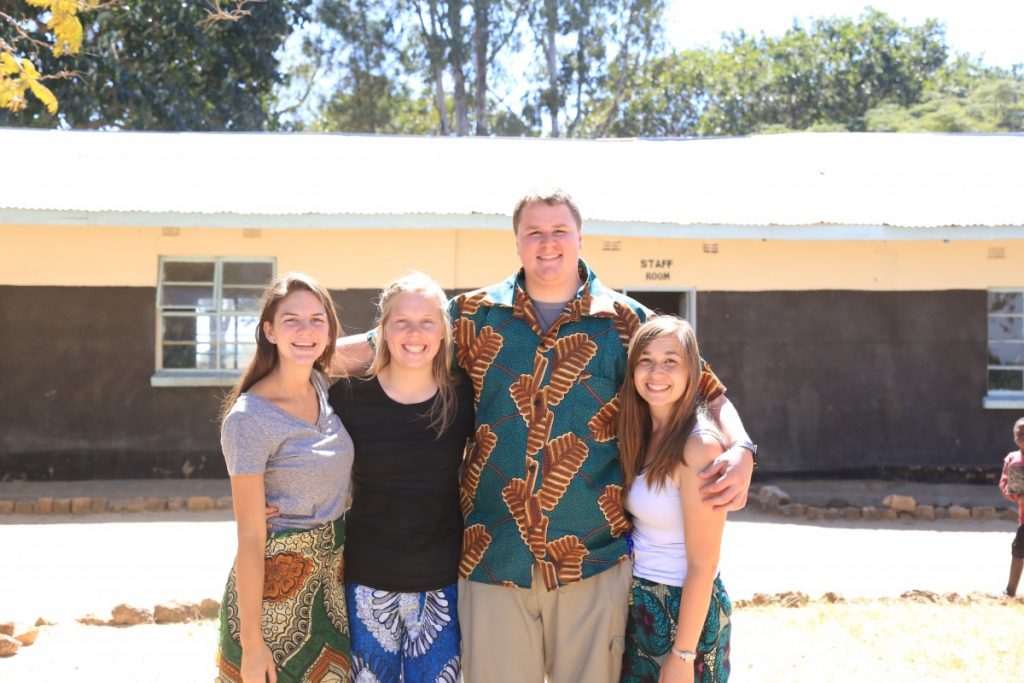

The room that Andrew, Justin, Sam and I stayed in at Fawlty Towers for a week. The coincidence was greatly appreciated, and made the hostel feel a little more like home.

The journey home is an interesting one for me, because at the current moment I don’t totally know what’s next: I have a home in Spokane for at least another year with some incredible guys; but with a Bachelor’s degree from Gonzaga in hand, there is nothing officially tying me to Spokane. Moving back home was an option, but in so many ways moving on and moving out has always been a little bit of a difficulty for me.

You’ve all read the descriptions of the convent that became our home: the piecework kitchen table collected from classroom tables we shared for breakfast, the hallways that afford no relief from any noise in the convent, and the mustard yellow walls that soon became filled with our memories, lessons, and goals for our time together in Zambezi. For the last week, while we’ve been in Livingstone and on safari in Botswana, we haven’t had the same comfort – while Fawlty Towers served as an incredible home for us in the short term, it definitely lacked the space and memories that helped it feel like home.

Often at breakfast in Zambezi, I would find a seat on a specific side of the table. The wall behind me held affirmations from the first week here: “_______, I think you are….”, with a multitude of ideas from the beginnings of our journey together and how we showed our best selves to those around us. In front of me was a different kind of affirmation wall – one filled with our goals for ourselves for the trip, and how people could best challenge us in the coming weeks.

The mornings were a great time to look at these posts and remember that so many of us had struggles that we would need help with. For example:

“_______ is going to work on not taking his stress out on others.”

“_______ is working on making mistakes and embracing each failure as a learning opportunity.”

“_______ is working on listening more than speaking and taking time for himself.”

“_______ is working on being wholly herself with no apologies for who she is.”

My eyes would float through this list every morning as we read the blog posts from the day before, and I couldn’t help but think how so many stories reflected the struggles each individual were working on. Then, my eyes catch mine, situated at the bottom of the group.

“Matt is trying to work on genuinely experiencing emotions while here – please help him work on this!”

Soon after beginning this journey, I came to recognize that the emotions associated with this trip are experienced in vastly different ways than the emotions we feel in the States. Often times, I found myself as the group member who walked between the larger groups of students. I was the one who stared out the window, who listened more than he talked, and was often one who asked how things were going instead of answering. While I had always considered empathy to be one of my strengths, I found myself struggling to understand my own emotions, especially in the early days of this journey, and I couldn’t help but think that I was inhibiting my own goal.

Places like the Kabompo River give great opportunities to reflect. Get it? Reflect?

In a couple of early conversations with faculty and friends, I mentioned how easy it was to experience what felt like the entire emotional spectrum in a single day. Compared to the comforts of Spokane, where days could go by on roughly the same emotional level, and emotions quickly became exhausting. For someone who was used to flying though the day on autopilot, the challenge came in recognizing that each individual emotion carried weight and significance to our journey. Even more important? The similar emotional journeys of the twenty Zags and two powerful women I shared the table with every day, all of which had just as much importance in our time in Zambezi.

Leaving for this journey two days after graduation was extremely difficult. In the rush to wrap up my final year at Gonzaga, I left a lot of conversations unfinished or unspoken. It took me a while to fall in love with Gonzaga, but once I did I fell hard – and it was difficult to imagine myself anywhere else with any other people.

So, I did what I usually did: I disconnected. I ran. I let people know that I was starting to get comfortable again, and immediately used it as an excuse to leave, even though I knew that growing remained to be done at home. Just as quickly as the years of my undergraduate career passed by, I passed by as well – half moved out of 1004.5 E Sinto, exchanging awkward goodbyes with my friends and roommates who had become my biggest support system, and knowing that by taking this journey, I would be missing out on another month with all of them. For the first time, saying goodbye to friends felt wrong, for I knew the next time we would all be reunited was in the very indefinite future.

And then, I left.

The best (and sometimes most challenging part) about this community is that it’s just about impossible to hide things from those around you. For the first couple of days, it was really easy to deflect and convince people that everything was okay. But, as time does, it gets out the truth. Soon, dinner conversations became more insightful and in-depth, challenging us to search out the answers we were suppressing. In numerous conversations under the stars on creaky benches, it all came out – homesick, not finding the space to process the ways God was yelling at us, feeling disconnected, being lost. My personal favorite: wondering why I was there, why I was anywhere, what was mine to do in the world.

Every question I had been ignoring or pushing down for the last three months, meet the world. World, meet questions.

In the health classes we taught, the passion of our students for the subject matter inspired us every day, and often drew eye rolls and laughter in team reflections later on. Somehow, nearly every conversation we would have over three weeks would take a turn into some aspect of sexual health or education, often instigated by the group of 20-something boys in the back corner or 81-year-old Chiwala in the front right chair.

As awkward and random as their questions could be, they always drew laughs – with students laughing the hardest. For them, it was easy to find joy in every situation, knowing that together they were learning and having an experience that comes around once in a rare while. They embraced the awkward and the small failures in the grand scheme of the experience, laughing and rolling with the punches.

Just like we were – even though I couldn’t see it right away.

In our three weeks we shared in joy at breakthroughs in classes, frustration in the unreliable power grid that often led to last-minute changes of plans, and sorrow with community members that became friends as they grieved. Some of us, more than others, shared all these emotions at once in taking trips across rivers to villages to teach classes, only to find school closed. We would settle for a Coke instead and share in pained laughs about the day, but were thankful for the companionship experienced in the process.

Leaving Zambezi was hard. It was emotionally hard, physically hard, and hard to know when the next time I’ll return is. Four years ago, I left the comforts of my family home to move to Gonzaga and quickly found out that life doesn’t stay the same once you leave. In the same way, I know that my memories of Zambezi won’t be the same as past and future groups, but the stories we tell will piece together a narrative that continues to weave us together over time.

Pro tip: if you ever get the chance to stand in one of the world’s largest waterfalls, the word “no” is immediately removed from your vocabulary.

But what is most important is the ways that the experience of leaving and growing apart and together all at once change me. With our time in Livingstone, there have been incredible highs and deep lows, often in the same day. I stood in the majesty of Victoria Falls, soaked by waterfall spray that hid the tears on my face, and laughed at the sheer beauty of falling water. A few hours later, standing on a bridge at the edge of the falls with a close friend, I was asked if I was doing okay with it all.

Minutes earlier, I had looked down at the water rushing out of the collection pool some 500 feet below us and thought about the distance to the water below. I’ve been quick to think of the worst possible situation in the last three months, and often those thoughts crowd out reason and overwhelm me. Close friends have gotten familiar with this and know the importance of time in coming out of a funk, but here on the other side of the world it can be hard to remember that safety nets are large and wide.

In that moment, I was overwhelmed. But just like some thoughts keep omnipresent, over time these can change – I found myself wondering why I was worried about the worst things that could happen, instead of enjoying the moment for the simple memories it would bring.

The question was repeated: “Matt – are you doing okay with it all? What’s going on in your head?”

I kept my eyes down for a few seconds, thinking about the answer. “I don’t know if I am right now, but I will be okay soon,” I managed to say. And, for the first time in a long while, I’m comfortable with that answer.

I don’t know if I’m okay right now, or will be once we land in the States, or five years from now. A lot has happened here, and these experiences are definitely something that will take time to process. There have been answers to questions I’ve long been asking, but often these are simply more questions that will also have to be answered someday.

Instead, I’m learning to embrace that process. For so long in Zambezi, we didn’t have answers to all the questions we were asked, and I probably have more questions now that we’re leaving than when we landed – but that’s okay. I’m okay with that, and that I won’t be the one to answer those questions in the future.

I’m working on being emotionally authentic – please continue to help me with that. Call me out on the ways I hide or run away, because I’ve spent the last month finally unable to hide from questions. Challenge me, just like so many Zambians and Zags have continued to do, and as they will in the future as well.

There are questions that will continue to remain unanswered. I’m okay with that. Questions that are mine to answer will come in time, and I’ll know when it happens, but for now I’m okay with still looking for answers and finding more questions along the way. Zambezi, I look forward to hearing how you challenge students in the coming years, and I cannot thank you enough for showing me the power of true emotions and the healing that can come in admitting you’re struggling.

Mama Josephine said it best – “We will be there soon, but it is still far away.” You’ll forever be close to my heart, and though I don’t know when, I look forward to meeting you again in another time.

Tunasakwilila mwane, Zambezi. Moyowove cheka – see you again soon.

Matthew Clark

Gonzaga Class of 2016

As we trudge down the airstrip to meet the planes waiting to take us to Livingstone, I drag my feet reluctantly. Minutes ago, I had hugged Katendi goodbye. I had felt hot tears welling in my eyes in front of my fellow zags for what feels like the thousandth time. I had walked through our funny yellow home, its dusty shelves now empty of our collected belongings, taping up a note for the 2017 Zam Fam in the well-loved closet. Leaving Zambezi seems big–colossal, monumental, even. And it is for me. I have learned and grown here for two summers now, and I will not easily forget the sandy path from the convent to Jasper’s shop where I went nearly every day for a ginger beer. But the last lesson Zambezi offered me was one that reminded me how inconsequential I am here. Very appropriately, it came in the form of a little boy named Wisdom. As I took my last steps on Zambezi dirt for at least the foreseeable future, he stuck a sweaty hand in mine and asked, “what’s your name?”

As we trudge down the airstrip to meet the planes waiting to take us to Livingstone, I drag my feet reluctantly. Minutes ago, I had hugged Katendi goodbye. I had felt hot tears welling in my eyes in front of my fellow zags for what feels like the thousandth time. I had walked through our funny yellow home, its dusty shelves now empty of our collected belongings, taping up a note for the 2017 Zam Fam in the well-loved closet. Leaving Zambezi seems big–colossal, monumental, even. And it is for me. I have learned and grown here for two summers now, and I will not easily forget the sandy path from the convent to Jasper’s shop where I went nearly every day for a ginger beer. But the last lesson Zambezi offered me was one that reminded me how inconsequential I am here. Very appropriately, it came in the form of a little boy named Wisdom. As I took my last steps on Zambezi dirt for at least the foreseeable future, he stuck a sweaty hand in mine and asked, “what’s your name?”

I plunged my hands into the 25-liter bucket of cold, sticky oochi mixed with honeycomb and scooped as much as I could into the filtration system (another 25-liter bucket with a corrugated base resting on top of a larger empty bucket.) With Jeff’s GoPro camera strapped to my head, I was ready for the action of filtering and purifying some fresh oochi-(Luvale for honey). The oochi was smooth and dripped off of my hands with each motion. A Zambian beekeeper, my guide in this process, was meticulously following my movements in case I dropped any of the honeycomb mixture, which I did… quite often. After several tries, I decided that maybe this very involved demonstration would be better left to the professionals. So instead I reached my hand back into the bucket and grabbed a clump of oochi and honeycomb and put it right in my mouth. I chewed the glob in delight and spit out the remaining wax as the sweet taste of oochi lingered on my taste buds.

I plunged my hands into the 25-liter bucket of cold, sticky oochi mixed with honeycomb and scooped as much as I could into the filtration system (another 25-liter bucket with a corrugated base resting on top of a larger empty bucket.) With Jeff’s GoPro camera strapped to my head, I was ready for the action of filtering and purifying some fresh oochi-(Luvale for honey). The oochi was smooth and dripped off of my hands with each motion. A Zambian beekeeper, my guide in this process, was meticulously following my movements in case I dropped any of the honeycomb mixture, which I did… quite often. After several tries, I decided that maybe this very involved demonstration would be better left to the professionals. So instead I reached my hand back into the bucket and grabbed a clump of oochi and honeycomb and put it right in my mouth. I chewed the glob in delight and spit out the remaining wax as the sweet taste of oochi lingered on my taste buds.