*Disclaimer: We are healthy. We don’t need a doctor. Read on to find out more.

In the two weeks since we’ve left the States, I feel like we’ve settled in to our home here. Classes are underway, we still have managed to avoid the Zambian bug for the most part (though it might be finally making an appearance), and the communal learning has finally commenced.

And yet, I still feel uneasy every time the health team heads out into Zambezi, outlying communities, or starts our 9 am class in the church hall.

For the last four months, the health team has worked to create a curriculum that not only covered basic topics that were important to general health and safety, but also addressed relevant needs in the community here. First aid, water safety, pregnancy questions and germs are pretty universal topics, but we also wanted to save a lot of time for conversations with classes about the information they wanted to learn. Instead of preaching what we believed was most applicable, we wanted to serve as a resource and be a tool for them to learn with to become community health ambassadors.

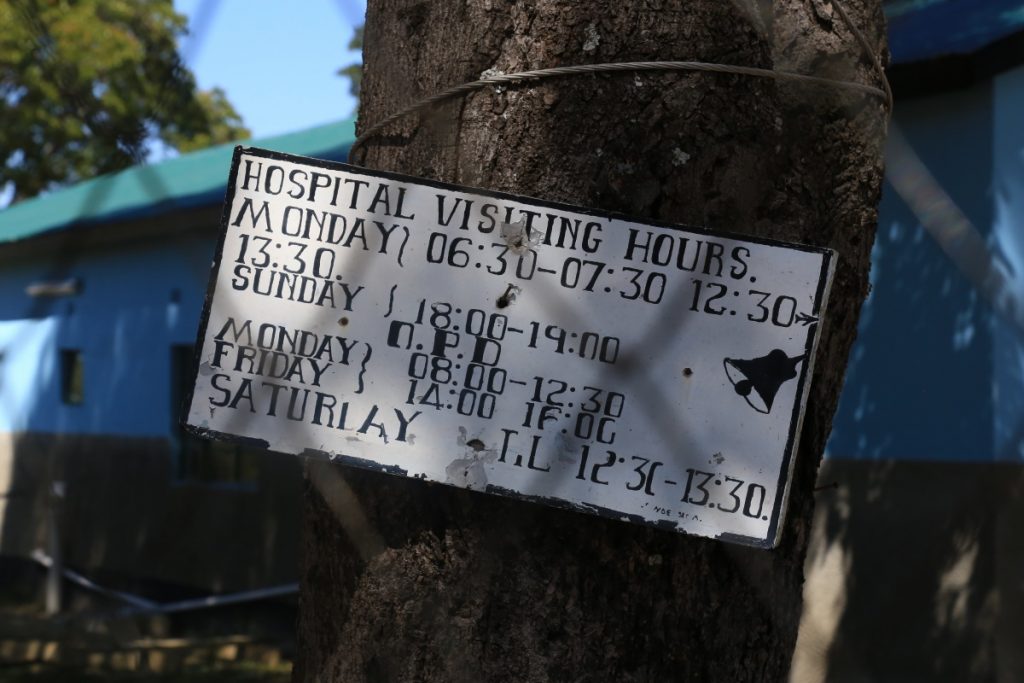

In our first week of classes, we traveled to a rural village school for a talk on the importance of education and puberty, visited both the Zambezi Hospital and a rural health clinic and arranged for visits to learn practices at both, and conducted classes in Zambezi and Dipalata on a variety of topics. We were excited to finally begin in Zambia, and couldn’t believe it was time to get started.

Except, like most plans in Zambia, things changed.

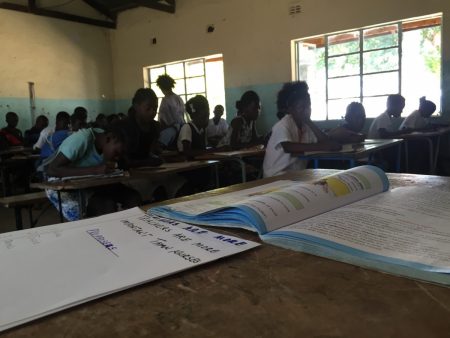

The students at the school we visited spoke little English, and much of the lessons were conducted through a translator. While this made the information more accessible to students, I couldn’t help but feel it increased the distance between us and the people we were trying to connect with.

Planned visits to the hospital and clinic on Friday both ended in less than ideal ways, as the doctor at the clinic was absent (fetching more vaccines for children) and the head nurse we had been in contact with at the hospital was out sick.

Our classes have been full of lively conversation, with each class focusing on a topic of our choosing and one topic of the community’s choosing. Often, these classes are discussion based, with myth-busting and fact-finding taking the majority of our time together. But for as much as our students have learned, I can’t help but feel like we are still unintentionally put on a pedestal here.

Because we are students from America – the land of opportunity and endless knowledge – it’s believed that we have answers for everything. Our community classes are built with the intent of spending half of the time in discussion about their chosen topics after we have had a chance to consult a few health manuals, but they still appear to take our suggestions as law. The problem of the white savior complex has been common in conversations with previous Zambezi students and staff, but experiencing it firsthand is a much different situation.

I’m fresh out of Gonzaga and have already gone through the medical school application gamut once, and I feel like now I’m living the scenario questions that they give you when you apply. To quote the secondary application for the University of Virginia School of Medicine (from where I am still awaiting a letter telling me that I was rejected, considering class starts next month): “How would you best approach bringing medical knowledge to a community that doesn’t necessarily share your beliefs or traditions?”

In our recent weekend trip, we stopped off in Chinyingi, a nearby community to see a suspension bridge and mission hospital. Upon reaching the hospital, we learned that only one patient was currently at the hospital for treatment, and the hospital was undergoing renovations to update it and make it as functional as possible. However, the hospital employed just one nurse, and no doctors.

We met the priest for the Chinyingi parish, Father Matthew, and his eyes lit up when Jeff explained that one of the teams we brought was a health education team. “Send us a doctor,” he said. “Send us a doctor, send us nurses. Come stay here. We will host you and support you while you’re here, we just need you to send us a doctor.”

Again – just because we are from America, the land where anything is possible and endless opportunity keeps the doors open.

The health team really struggled with not approaching our classes our excursions with a “white savior” complex – we’re not medical professionals, we don’t know all of this information by heart, we just used resources available to us and tried to find information that we thought would be useful to the people of Zambezi, but we also wanted to make sure that our classes were tailored to the things that community members wanted to learn.

I have another couple of years to work out the answer to that initial question on paper, but for the next two weeks that’s the situation we’re living: We’re trying to avoid preaching health practices, framing information in the context of our location without coming off as the pompous kids who think they’re making a difference.

Working together with Moira, Molly, Hayley and Justin is inspiring because they keep our group focused. Their drive for grounding information and practice in a realistic way for the people of Zambezi has made conversations much more approachable with our students, and using resources available here has proved to be a struggle that gives rare and great triumphs.

Yes, we are different because of the color of our skin, and our location of origin, and the opportunities that are readily available. But these coincidences that landed me in America and Gonzaga could have just as easily dropped me in the middle of Zambezi, seeking out knowledge at every turn. While we have access to information at the literal tap of our fingers, working with the community here has given me a new appreciation for not only the varying sources of knowledge, but the drive of Zambians to continually acquire knowledge. Everyone I’ve met here so far has seemed content with what they know, which inspires me to keep asking questions.

I’m 22. I don’t know everything, which is probably something that is odd to hear (or read) a 22-year-old say (or type). But after experiencing the white savior complex, and struggling to rationalize it as the availability of resources, I can’t help but be inspired to keep striving to learn from everyone and everything around me.

How do you approach bringing medical knowledge to a community that doesn’t necessarily share your beliefs or traditions? You don’t. You can’t. All you can do is come in with an understanding of your beliefs, and work to share them with those who have differing beliefs. Learning doesn’t occur when beliefs change, but when they are shared. And that is what I’m doing here.

Kisu mwane,

Matthew Clark

Class of 2016

PS: Mom, happy birthday in advance, since I won’t be able to say it next week. As your present, here is a picture of me, smiling, and doing fun things. Thanks in so many ways for every opportunity you’ve given me, I love you to the moon.

PS #2: Mama Phillips, Davis says he loves, you, happy anniversary, and happy birthday (the triple whammy)!

PS #3: Trevor, Rosie, Kelly, Andy, Carlee and the rest of the Sinto Squad: miss you guys every day and can’t wait to hear about all of your post grad adventures. Counting the endless days until I get to see you all again.

Its kind of ironic that after ten days being away from the States, countless conversations, and witnessing simplicity of such a happy place, I struggle to fully accept where I am at. I give credit to the relationships that transcend my current place in time to those who walked the rugged sandy roads, irregularly power surging halls of the convent, and the undertone of love pulsing from handshakes and greetings surmounting to ten years of cross-cultural interactions.

Its kind of ironic that after ten days being away from the States, countless conversations, and witnessing simplicity of such a happy place, I struggle to fully accept where I am at. I give credit to the relationships that transcend my current place in time to those who walked the rugged sandy roads, irregularly power surging halls of the convent, and the undertone of love pulsing from handshakes and greetings surmounting to ten years of cross-cultural interactions. At dinner tonight in the living room of our convent lit by the unequally distributed power lighting and yellow walls hugging our family, we set the multiple, oddly shaped and configured wooden desk tables for what is to be a meal full of more stories and laughter. Upon the conclusion of dinner, we recognize an esteemed individual who has made an impact on our time here in Zambezi. Father Dominic, received affirmation regarding his selfless heart, compassionate spirit, and his ability to attack each day with a vigor that inspires us to do the same. Father Dominic quelled some of the initial nerves I had regarding my time in Zambezi by uniting our family in the first moments in Africa, becoming my first familiar face here. I hold this quote dear to my time in this remarkable place: “It is not the length of life, but the depth of life” by Ralph Waldo Emerson. With Father Dom’s departure quickly approaching, I am challenged again to make the most of the deep connections Zambezi has to offer for the short time that I am here.

At dinner tonight in the living room of our convent lit by the unequally distributed power lighting and yellow walls hugging our family, we set the multiple, oddly shaped and configured wooden desk tables for what is to be a meal full of more stories and laughter. Upon the conclusion of dinner, we recognize an esteemed individual who has made an impact on our time here in Zambezi. Father Dominic, received affirmation regarding his selfless heart, compassionate spirit, and his ability to attack each day with a vigor that inspires us to do the same. Father Dominic quelled some of the initial nerves I had regarding my time in Zambezi by uniting our family in the first moments in Africa, becoming my first familiar face here. I hold this quote dear to my time in this remarkable place: “It is not the length of life, but the depth of life” by Ralph Waldo Emerson. With Father Dom’s departure quickly approaching, I am challenged again to make the most of the deep connections Zambezi has to offer for the short time that I am here.

At 6am, the flight I was on left the red, dirt runway aboard a six passenger plane. We donned ear protection and seatbelts. We passed over the Kafue River and Kafue National Park- some groups spotted hippo, elephants and impala below their lovely flight. Some pilots did tricks, and passenger stomachs dropped and dipped with nausea.

At 6am, the flight I was on left the red, dirt runway aboard a six passenger plane. We donned ear protection and seatbelts. We passed over the Kafue River and Kafue National Park- some groups spotted hippo, elephants and impala below their lovely flight. Some pilots did tricks, and passenger stomachs dropped and dipped with nausea.