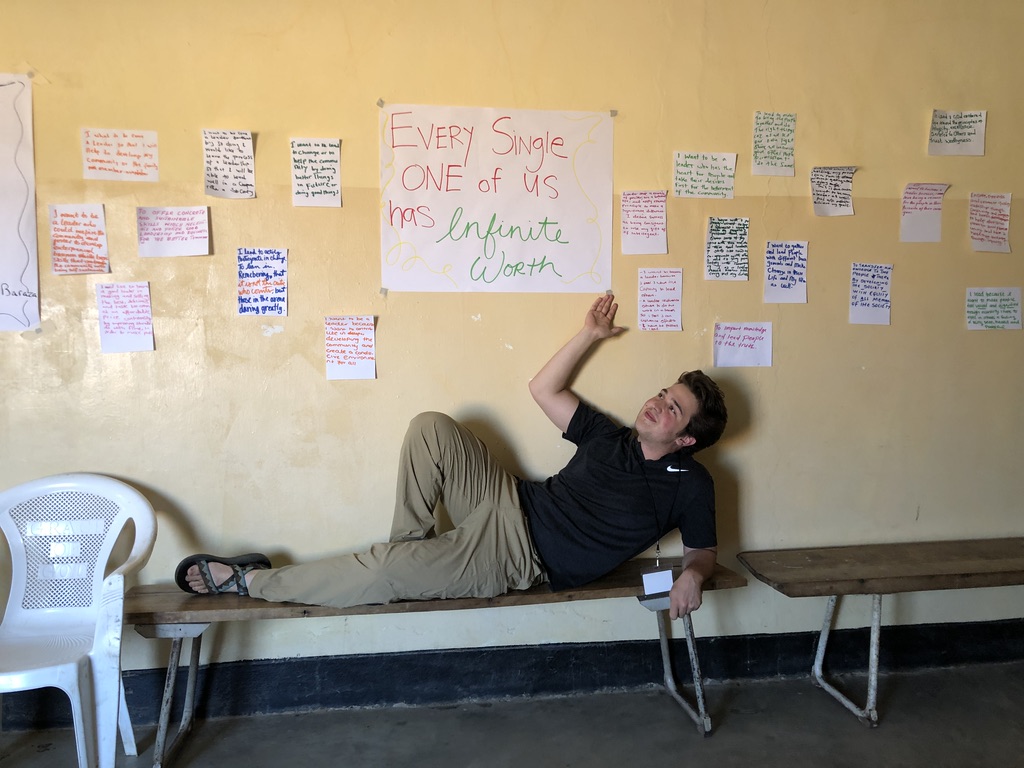

(Unrelated photo that hopefully kinda gets you into a reflective mood)

Anyone who knows me knows that I am reflective: constantly and to a fault. In preparation for this trip, we congregated in Gonzaga’s student chapel during finals week for a commissioning service. During the service, we took part in a reflective activity in which we took a scrap of paper, and wrote a hope for the trip on one side, and a fear on the other. We then collected the papers and redistributed them so that each member of this group would mindfully hold the hopes and fears of another member in their prayers and thoughts, knowing also that their own hopes and fears were being held.

The fear that I noted in that moment was essentially that I would get in the way of myself, that my constant introspection would make it difficult for me to be present during my time here in Zambia. As I consistently face interpersonal and intercultural challenges each day, some new and others increasingly familiar, I have gotten in my own way more than once. Now rest assured, I do not intend for the entirety of this post to be consumed by admittedly over-critical self analysis; probably just 80% of it.

I am honored to have spent a significant amount of time with Josh(ua Paul Armstrong, Ph.D.) since beginning my time at Gonzaga, breaking bread with him on a quasi-weekly basis over the course of the last semester. Due to our relational proximity, he has grown quite aware of the difficulty I have giving grace to myself, and has reminded me several times in the recent weeks to “feel free,” a phrase he has drawn from his time with Zambians. He has even encouraged me to write the phrase on my arm. Whether or not such a suggestion was in jest, I’ve taken to doing so in recent days.

Now, feel free to do what exactly? When I hear the phrase, I feel it suggests an ellipsis (…) rather than a period (.). However, the two words are complete on their own. Feel free: experience freedom- from pressures, excessive guilt, shame. In other words, access grace. For me, that means exploring and pursuing understanding of the grace of God through my guy Jesus. A deep question which I will not pretend to understand, or attempt to discern at this time (maybe later?). Grace is tough, both for myself and others, but it is key to operating free from anxiety, especially in this cultural context.

I know that talk of the differences between “hot- and cold-climate” cultures* has made its way into the blog and I will reference the concept again, as I’ve found an understanding of the dichotomy relevant to my experiences this month. I come from a “cold-climate” culture that values punctuality and planned, organized social interaction. That’s not as much the case here in “hot-climate” Zambezi. With my desire for control and predictability, this new lifestyle of spontaneity does not come easily to me.I am immensely grateful for the people that I work with here, as they have been integral to this season of my journey in understanding and experiencing freedom. While I have attempted to coordinate details of our computers class to an unnecessary degree, they remind me both to generally chill out, and to embrace the flowing nature of life and timing here. They (special shoutouts to Alea Chatman, Emma Cheatham, Sammi Rustia and the GOAT TA Ethan “Mwane Kane” Kane) have also been gracious in embracing an exchange of work time that has allowed me to forgo days of teaching in order to experience different parts of Zambia- namely the rural village of Kalundola (referenced by Daniel Li in his post “Kalundola Bound; Liberations Bound”) and the crowded mine town of Solwezi.

I am joying Zambia very much (@ Georgie’s Bar and Grill en route to Solwezi)

While I’m on the subject of Solwezi, I may as well explain why the dynamic quintet of Josh, (Father Patrick) Baraza, Sammi, Rachel Walls and myself made the six hour drive to get there. Solwezi is a larger town, described perhaps by optimists as bustling and developed, and by others as an example of the difficulties that arise from the enticing promise of jobs offered by an out-of-country mining company which is taking advantage of the rich mineral deposits located in Zambia (copper, gold, cobalt, uranium). There’s plenty to unpack there, especially as there is movement towards development of mines in and around Zambezi, but I’ll leave that discussion up to you and your Zambezi Zag of choice.

The trip to Solwezi took place primarily to strengthen the connection between GU and the Catholic Church in this region via a meeting between Josh, Fr. Baraza and the Bishop of the Diocese of Solwezi. We also had a chance to connect with several of Josh’s friends, whether intentionally (with Fathers Stephen and Sydney, who hosted us overnight, and Robinson, a Solwezi resident from Zambezi who provided valuable insight on the mines over dinner) or through providence (like running into Staff Sergeant Chewe, who had helped with our car troubles returning from Kalundola a week earlier). Perhaps most immediately valuable was our visit to a supermarket, which yielded a wealth of products inaccessible in Zambezi, including coffee, chocolate, cheese, and PLEASE ANY CEREAL OTHER THAN KELLOGG’S CORN FLAKES which holds a truly impressive foothold in the rural Zambian breakfast cereal market. Having returned to the convent’s ambient cacophony, I am thankful for having had the opportunity to experience a change in rhythm.

An assortment of chitenge fabrics at a shop in Solwezi

However, while I appreciate the ability to experience unique parts of life in Zambia, I do feel a weight having sacrificed three days of class. Spending three weeks in Zambezi sounds look a lot of time, until I realize that we are two weeks into our time here. How can I really “feel free,” when there is so much to be done in this short time? I need to help teach computer basics to 60 or so students, complete readings and assignments for the courses we’re working towards in our time here, purchase gifts for my family and friends, explore the market, remember to be active, go to church, get rest, make time to reflect, and carry my weight on the group chore wheel. Oh, and I can’t forget to make some time for those spontaneous experiences! To make matters more complicated, I find increasing joy in the relationships I am developing amongst our Gonzaga group, and so deal with the added temptation to stay within my comfort zone and engage mostly with people in our group, rather than venturing out to pursue relationship with Zambians.

That is, after all, why I am here: to engage in intercultural relationships.

However, I question if three weeks is enough time to develop relationships. Is it worth pursuing others, knowing that I will likely never see most of them again on this Earth? (though my Facebook will be popping as soon as I get back) I struggle with this question, of whether it is worthwhile opening my heart to others for such a brief time. But what then, is enough time to justify opening one’s heart?

Even as I type these questions, I know that part of an answer is to “feel free.” Perhaps I need to just sit down, open my palms and spend time being with Brother Sitali, or Mumba the tailor, or Mama Katendi, or some of the young guys like Emmanuel, Abel or Samuel. Maybe I’ll stay for tea, who knows. Yeah, I’m definitely on to something there! Time to get out there and start being with others… after all we return to the United States in 11 days.

As that realization sets in for me, and our group, I hope that we begin or continue to explore what it really means to “feel free” here in Zambezi, to show grace and receive it for ourselves, to dive into relationship with folks here, even as our imminent departure quietly looms, and to let each day bring what it will.

Thank you to Josh, to Janeen, to Fr. Baraza for encouragement and grace. Thanks to my home team for your support in prayer and finances- B2Z has come to fruition. Thank you to my peers for their passion and creativity and kindness and curiosity and eloquence and accompaniment. Thank you to Father Yona for his hospitality. Thanks to Debby and his aerobics class for reminding me muscles in my legs that I forgot I have. Thanks to God for peace, safety and provision.

Proof I’m alive and well @Mom #JamboTime

As I look forward to a full Saturday with our Gonzaga group, the roller-coaster process of understanding and reflection continues.

TO YOU, THE READER: Thank you and congratulations for making it through this post! Wherever and whoever you are, I hope that you pursue what it means to feel free in your life. Freedom is always an option, and always worthy of pursuit.

Peace,

Bryce Kreiser

* Foreign to Familiar by Sarah A. Lanier (2000)

* Foreign to Familiar by Sarah A. Lanier (2000)

Early last semester I was in my advisor’s office, making us both feel uncomfortable with the number of tears I was attempting, but failing, to hold back with my sarcastic hand motions and notable “okayyy anyway”. I wept because I felt like I was in a constant free fall. I felt like the path I kept trying to walk on was crumbling beneath me, and there wasn’t anything to do but to fall; to cry. My advisor, with this gentle heart and awkward demeanor, said nothing but allowed the space for me to fall with someone. A couple weeks later I dropped by his office and he had a book for me, The Alchemist. He didn’t say much about it, but when I opened the front cover I stopped falling for just a moment. “Read whenever you’re ready, whenever that time arrives.” Well that time came, folks. My capacity to absorb the world around me without allowing myself to process reached its limit. My cup was full, but leaking.

Early last semester I was in my advisor’s office, making us both feel uncomfortable with the number of tears I was attempting, but failing, to hold back with my sarcastic hand motions and notable “okayyy anyway”. I wept because I felt like I was in a constant free fall. I felt like the path I kept trying to walk on was crumbling beneath me, and there wasn’t anything to do but to fall; to cry. My advisor, with this gentle heart and awkward demeanor, said nothing but allowed the space for me to fall with someone. A couple weeks later I dropped by his office and he had a book for me, The Alchemist. He didn’t say much about it, but when I opened the front cover I stopped falling for just a moment. “Read whenever you’re ready, whenever that time arrives.” Well that time came, folks. My capacity to absorb the world around me without allowing myself to process reached its limit. My cup was full, but leaking.

to face away from everyone still sitting in the back and drop his gift on the rover’s back bumper. After getting back on the road not-so-old-reliable broke down one last time and we had to call Fr. Yona to come rescue us, 25km or so from home. All 13 of us managed to squish into Yona’s Toyota Hilux and got home only a couple minutes after dinner. I know what you’re thinking but don’t worry, Cassius/MJ, the rooster, pumpkins, and maize were towed back by the military dudes (talk about a godsend, we really are indebted to them)- bag secured.

to face away from everyone still sitting in the back and drop his gift on the rover’s back bumper. After getting back on the road not-so-old-reliable broke down one last time and we had to call Fr. Yona to come rescue us, 25km or so from home. All 13 of us managed to squish into Yona’s Toyota Hilux and got home only a couple minutes after dinner. I know what you’re thinking but don’t worry, Cassius/MJ, the rooster, pumpkins, and maize were towed back by the military dudes (talk about a godsend, we really are indebted to them)- bag secured.

We expected the dinner at the priest’s house to be low key but we soon became aware that it was more like a huge party. Father Yona invited the Zambezi youth (community members ages 15-25) so that we would be able to interact with others in the community our own age. They brought huge speakers and microphones so that they could sing and dance with us. We each got to share a piece of our culture when they shared with us a popular dance in Zambia that involved A LOT of dancing with your hips and we in turn taught them the Cupid Shuffle and the Electric Slide. This sharing of traditions was such a fun way to allow us to meet even more friendly faces from the Zambezi community. The night continued with lip sync battles and dancing to Post Malone as well as One Direction with a Catholic Church Youth group. I can honestly say this was something that I never expected to do in Zambezi, or even at home. To quote Ethan, “That was the sauciest youth group I have ever seen.” Megan wanted me to add that she even got pulled up on stage and was serenaded to and even received a “proposal!”

We expected the dinner at the priest’s house to be low key but we soon became aware that it was more like a huge party. Father Yona invited the Zambezi youth (community members ages 15-25) so that we would be able to interact with others in the community our own age. They brought huge speakers and microphones so that they could sing and dance with us. We each got to share a piece of our culture when they shared with us a popular dance in Zambia that involved A LOT of dancing with your hips and we in turn taught them the Cupid Shuffle and the Electric Slide. This sharing of traditions was such a fun way to allow us to meet even more friendly faces from the Zambezi community. The night continued with lip sync battles and dancing to Post Malone as well as One Direction with a Catholic Church Youth group. I can honestly say this was something that I never expected to do in Zambezi, or even at home. To quote Ethan, “That was the sauciest youth group I have ever seen.” Megan wanted me to add that she even got pulled up on stage and was serenaded to and even received a “proposal!”